I previously wrote METHYLATION CYCLE, GENETICS, B VITAMINS in which I considered in-depth how the Methylation Cycle functions, how genetics affect metabolic pathways, and how B vitamins (including vitamin B12, folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B2) are used in Methylation Cycle pathways. In today’s article, I take an in-depth view of what you need to know about vitamin B12, including the effects of not having sufficient amounts of Vitamin B12 in the body.

I previously wrote METHYLATION CYCLE, GENETICS, B VITAMINS in which I considered in-depth how the Methylation Cycle functions, how genetics affect metabolic pathways, and how B vitamins (including vitamin B12, folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B2) are used in Methylation Cycle pathways. In today’s article, I take an in-depth view of what you need to know about vitamin B12, including the effects of not having sufficient amounts of Vitamin B12 in the body.

Vitamin B12 is one of eight B vitamins. It is the largest and most structurally complicated vitamin. It consists of a class of chemically related compounds (vitamers), all of which show physiological activity. It contains the biochemically rare element cobalt positioned in the center of a chemical ring structure.

Vitamin B12 (also called cobalamin) is a water-soluble vitamin that is involved in the metabolism of every cell of the human body. It is a cofactor in DNA synthesis, and in both fatty acid and amino acid metabolism. It is particularly important in the normal functioning of the nervous system via its role in the synthesis of myelin and in the maturation of developing red blood cells in the bone marrow.

YOUR NEED FOR VITAMIN B12

Vitamin B12 deficiency is thought to be one of the leading nutritional deficiencies in the world. An extensive 2004 study showed that deficiency is a major health concern in many parts of the world, including the North America, Central and South America, India, and certain areas in Africa. It is estimated that 40 percent of people may have low levels of vitamin B12.

Vitamin B12 affects your mood, energy level, memory, nervous system, heart, skin, hair, digestion and more. It is a key nutrient regarding adrenal fatigue and multiple metabolic functions including enzyme production, DNA synthesis, and hormonal balance.

Because of vitamin B12’s extensive roles within the body, a vitamin deficiency can show up in many different symptoms, such as chronic fatigue, mood disorders such as depression, chronic stress, and low energy.

SOURCES OF VITAMIN B12

The only organisms to produce vitamin B12 are certain bacteria and archaea. Some of these bacteria are found in the soil around the grasses that ruminants eat. They are taken into the animal, proliferate, form part of their gut flora, and continue to produce vitamin B12.

Products of animal origin such as beef (especially liver), chicken, pork, eggs, dairy, clams, and fish constitute the primary food source of vitamin B12. Older individuals and vegans are advised to use vitamin B12 fortified foods and supplements to meet their needs.

Commercially, Vitamin B12 is prepared by bacterial fermentation. Fermentation by a variety of microorganisms yields a mixture of methylcobalamin, hydroxocobalamin, and adenosylcobalamin. Since multiple species of propionibacterium produce no exotoxins or endotoxins and have been granted GRAS status (generally regarded as safe) by the United States Food and Drug Administration, they are the preferred bacterial fermentation organisms for vitamin B12 production.

Commercially, Vitamin B12 is prepared by bacterial fermentation. Fermentation by a variety of microorganisms yields a mixture of methylcobalamin, hydroxocobalamin, and adenosylcobalamin. Since multiple species of propionibacterium produce no exotoxins or endotoxins and have been granted GRAS status (generally regarded as safe) by the United States Food and Drug Administration, they are the preferred bacterial fermentation organisms for vitamin B12 production.

Methylcobalamin and 5-deoxyadenosylcobalamin are the forms of vitamin B12 used in the human body (called coenzyme forms). The form of cobalamin used in many some nutritional supplements and fortified foods, cyanocobalamin, is readily converted to 5-deoxyadenosylcobalamin and methylcobalamin in the body.

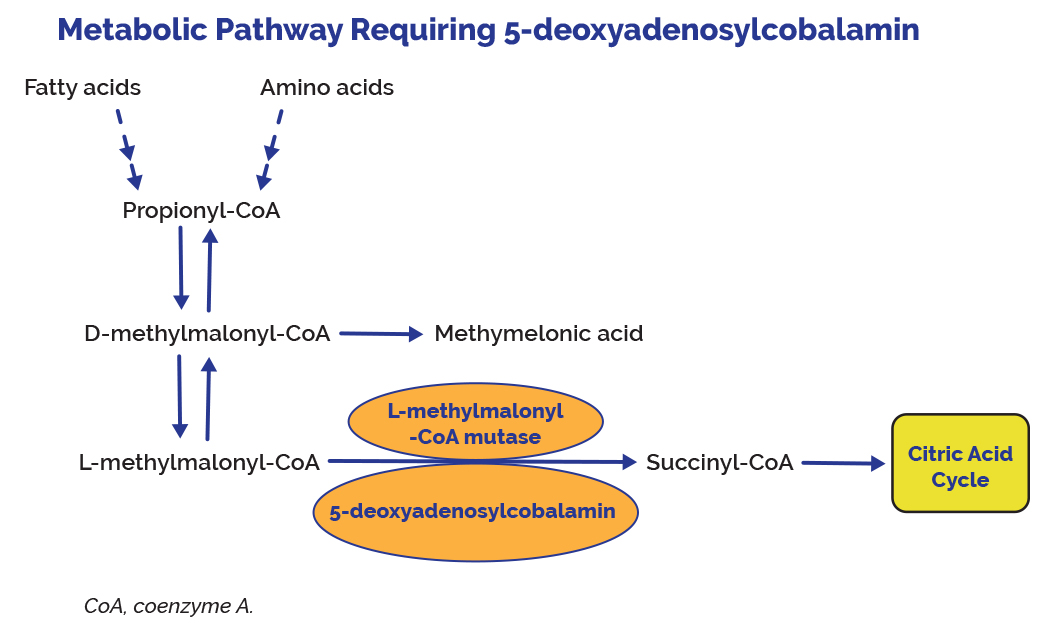

Hydroxocobalamin is the direct precursor of methylcobalamin and 5-deoxyadenosylcobalamin. In mammals, cobalamin is a cofactor for only two enzymes, methionine synthase (MS) and L-methylmalonyl-coenzyme A mutase (MUT).

Unlike most other vitamins, B12 is stored in substantial amounts, mainly in the liver, until it is needed by the body. If a person stops consuming the vitamin, the body’s stores of this vitamin usually take about 3 to 5 years to exhaust. Vitamin B12 is primarily stored in the liver as 5-deoxyadenosylcobalamin, but is easily converted to methylcobalamin.

ABSORPTION OF VITAMIN B12

Vitamin B12, bound to protein in food, is released by the activity of hydrochloric acid and gastric protease in the stomach. Intestinal absorption of vitamin B12 requires successively three different protein molecules: Haptocorrin, Intrinsic Factor and Transcobalamin II. If there are deficiencies in any of these factors absorption of Vitamin B12 can be seriously decreased.

When vitamin B12 is added to fortified foods and dietary supplements, it is already in free form and, thus, does not require the separation from food protein step. Free vitamin B12 then combines with intrinsic factor, a glycoprotein secreted by the stomach’s parietal cells, and the resulting complex undergoes absorption within the distal ileum by receptor-mediated endocytosis.

Approximately 56% of a 1 mcg oral dose of vitamin B12 is absorbed, but absorption decreases drastically when the capacity of intrinsic factor is exceeded (at 1–2 mcg of vitamin B12).

VITAMIN B12 DEFICIENCY

Vitamin B12 deficiency can be difficult to detect, especially since the symptoms of a vitamin B12 deficiency can be similar to many common symptoms, such as feeling tired or unfocused, experienced by people for a variety of reasons.

Vitamin B12 deficiency is commonly associated with chronic stomach inflammation, which may contribute to an autoimmune vitamin B12 malabsorption syndrome called pernicious anemia and to a food-bound vitamin B12 malabsorption syndrome. Poor absorption of vitamin B may be related to coeliac disease. Impairment of vitamin B12 absorption can cause megaloblastic anemia and neurologic disorders in deficient subjects. In some cases, permanent damage can be caused to the body when B12 amounts are deficient.

It is noteworthy that normal function of the digestive system required for food-bound vitamin B12 absorption is commonly impaired in individuals over 60 years of age, placing them at risk for vitamin B12 deficiency.

A diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency is typically based on the measurement of serum vitamin B12 levels within the blood. However, studies show that about 50 percent of patients with diseases related to vitamin B12 deficiency have normal B12 levels when tested. This can cause individuals to ignore taking in adequate levels of vitamin B12 with potential serious consequences.

FUNCTIONS AND ISSUES ASSOCIATED WITH VITAMIN B12 STATUS IN THE BODY

- Vitamin B12 or cobalamin plays essential roles in folate metabolism and in the synthesis of the citric acid cycle intermediate, succinyl-CoA.

- Vitamin B12 deficiency is commonly associated with chronic stomach inflammation, which may contribute to an autoimmune vitamin B12 malabsorption syndrome called pernicious anemia and to a food-bound vitamin B12 malabsorption syndrome. Impairment of vitamin B12 absorption can cause megaloblastic anemia and neurologic disorders in deficient subjects.

- Normal function of the digestive system required for food-bound vitamin B12 absorption is commonly impaired in individuals over 60 years of age, placing them at risk for vitamin B12 deficiency.

- Vitamin B12 and folate are important for homocysteine metabolism. Elevated homocysteine levels in blood are a risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). B vitamin supplementation has been proven effective to control homocysteine levels.

- The preservation of DNA integrity is dependent on folate and vitamin B12 availability. Poor vitamin B12 status has been linked to increased risk of breast cancer in some, but not all, observational studies.

- Low maternal vitamin B12 status has been associated with an increased risk of neural tube defects (NTD), but it is not known whether vitamin B12 supplementation could help reduce the risk of NTD.

- Vitamin B12 is essential for the preservation of the myelin sheath around neurons and for the synthesis of neurotransmitters. A severe vitamin B12 deficiency may damage nerves, causing tingling or loss of sensation in the hands and feet, muscle weakness, loss of reflexes, difficulty walking, confusion, and dementia.

- While hyperhomocysteinemia may increase the risk of cognitive impairment, it is not clear whether vitamin B12 deficiency contributes to the risk of dementia in the elderly. Although B-vitamin supplementation lowers homocysteine levels in older subjects, the long-term benefit is not yet known.

- Both depression and osteoporosis have been linked to diminished vitamin B12 status and high homocysteine levels.

- The long-term use of certain medications, such as inhibitors of stomach acid secretion, can adversely affect vitamin B12 absorption.

- Vitamin B12 is required for proper red blood cell formation, neurological function, and DNA synthesis.

MORE DETAILS ASSOCIATED WITH VITAMIN B12 STATUS IN THE BODY

3. Vitamin B12, bound to protein in food, is released by the activity of hydrochloric acid and gastric protease in the stomach. When synthetic vitamin B12 is added to fortified foods and dietary supplements, it is already in free form and, thus, does not require this separation step. Free vitamin B12 then combines with intrinsic factor, a glycoprotein secreted by the stomach’s parietal cells, and the resulting complex undergoes absorption within the distal ileum by receptor-mediated endocytosis. Approximately 56% of a 1 mcg oral dose of vitamin B12 is absorbed, but absorption decreases drastically when the capacity of intrinsic factor is exceeded (at 1–2 mcg of vitamin B12).

4. Pernicious anemia is an autoimmune disease that affects the gastric mucosa and results in gastric atrophy. This leads to the destruction of parietal cells, achlorhydria, and failure to produce intrinsic factor, resulting in vitamin B12 malabsorption. If pernicious anemia is left untreated, it causes vitamin B12 deficiency, leading to megaloblastic anemia and neurological disorders, even in the presence of adequate dietary intake of vitamin B12.

5. Vitamin B12 status is typically assessed via serum or plasma vitamin B12 levels. Values below approximately 170–250 pg/mL (120–180 picomol/L) for adults indicate a vitamin B12 deficiency. However, evidence suggests that serum vitamin B12 concentrations might not accurately reflect intracellular concentrations. An elevated serum homocysteine level (values >13 micromol/L) might also suggest a vitamin B12 deficiency. However, this indicator has poor specificity because it is influenced by other factors, such as low vitamin B6 or folate levels. Elevated methylmalonic acid levels (values >0.4 micromol/L) might be a more reliable indicator of vitamin B12 status because they indicate a metabolic change that is highly specific to vitamin B12 deficiency.

6. Vitamin B12 deficiency is characterized by megaloblastic anemia, fatigue, weakness, constipation, loss of appetite, and weight loss. Neurological changes, such as numbness and tingling in the hands and feet, can also occur . Additional symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency include difficulty maintaining balance, depression, confusion, dementia, poor memory, and soreness of the mouth or tongue. The neurological symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency can occur without anemia, so early diagnosis and intervention is important to avoid irreversible damage. During infancy, signs of a vitamin B12 deficiency include failure to thrive, movement disorders, developmental delays, and megaloblastic anemia. Many of these symptoms are general and can result from a variety of medical conditions other than vitamin B12 deficiency.

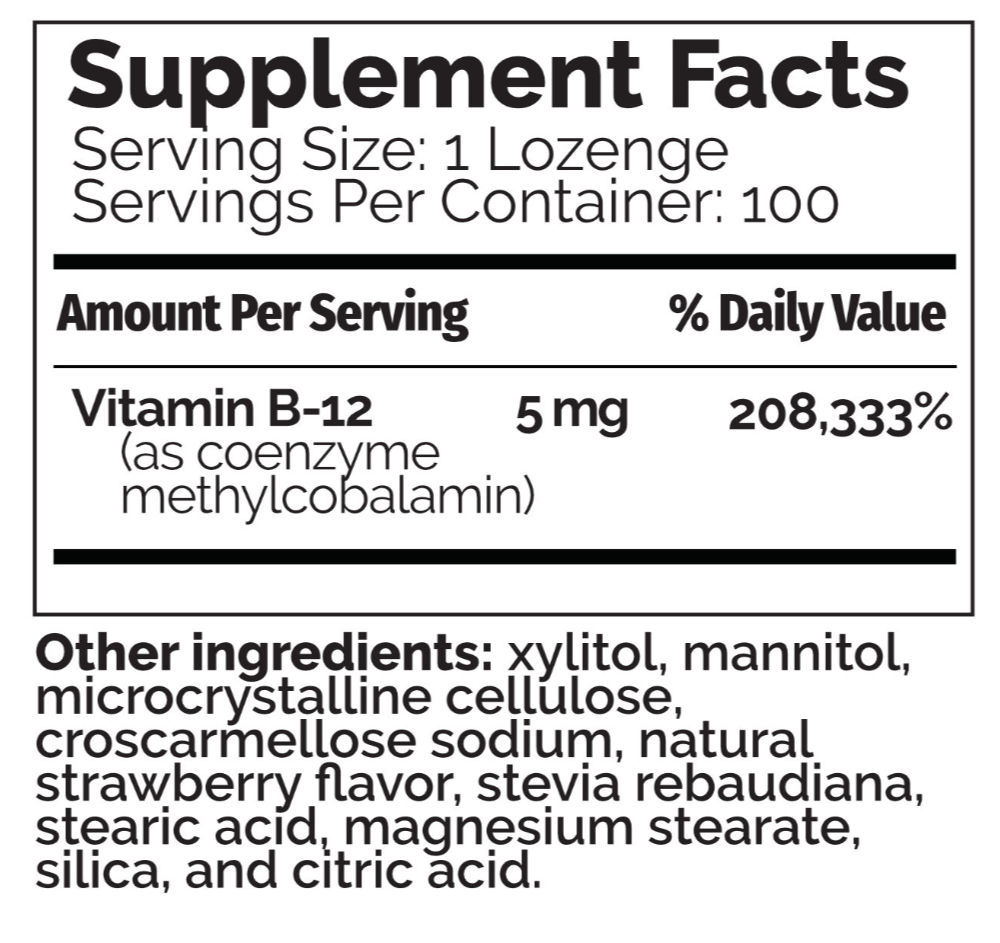

7. Typically, vitamin B12 deficiency is treated with vitamin B12 injections, since this method bypasses potential barriers to absorption. However, high doses of oral vitamin B12 can also be effective. The authors of a review of randomized controlled trials comparing oral with intramuscular vitamin B12 concluded that 2,000 mcg (I like 5,000 mcg) of oral vitamin B12 daily, followed by a decreased daily dose of 1,000 mcg and then 1,000 mcg weekly and finally, monthly might be as effective as intramuscular administration. Overall, an individual patient’s ability to absorb vitamin B12 is the most important factor in determining whether vitamin B12 should be administered orally or via injection. In most countries, the practice of using intramuscular vitamin B12 to treat vitamin B12 deficiency has remained unchanged.

8. Large amounts of folate can mask the damaging effects of vitamin B12 deficiency by correcting the megaloblastic anemia caused by vitamin B12 deficiency without correcting the neurological damage that also occurs. Moreover, preliminary evidence suggests that high serum folate levels might not only mask vitamin B12 deficiency, but could also exacerbate the anemia and worsen the cognitive symptoms associated with vitamin B12 deficiency. Permanent nerve damage can occur if vitamin B12 deficiency is not treated. For these reasons, folate intake from fortified food and supplements should not exceed 1,000 mcg daily in healthy adults.

Groups at Risk of Vitamin B12 Deficiency

The main causes of vitamin B12 deficiency include vitamin B12 malabsorption from food, pernicious anemia, postsurgical malabsorption, and dietary deficiency. However, in many cases, the cause of vitamin B12 deficiency is unknown. The following groups are among those most likely to be vitamin B12 deficient.

Older adults: Atrophic gastritis, a condition affecting 10%–30% of older adults, decreases secretion of hydrochloric acid in the stomach, resulting in decreased absorption of vitamin B12. Decreased hydrochloric acid levels might also increase the growth of normal intestinal bacteria that use vitamin B12, further reducing the amount of vitamin B12 available to the bodY.

Individuals with atrophic gastritis are unable to absorb the vitamin B12 that is naturally present in food. Most, however, can absorb the synthetic vitamin B12 added to fortified foods and dietary supplements. As a result, the IOM recommends that adults older than 50 years obtain most of their vitamin B12 from vitamin supplements or fortified foods. However, some elderly patients with atrophic gastritis require doses much higher than the RDA to avoid subclinical deficiency.

Individuals with pernicious anemia: Pernicious anemia, a condition that affects 1%–2% of older adults, is characterized by a lack of intrinsic factor. Individuals with pernicious anemia cannot properly absorb vitamin B12 in the gastrointestinal tract. Pernicious anemia is usually treated with intramuscular vitamin B12. However, approximately 1% of oral vitamin B12 can be absorbed passively in the absence of intrinsic factor, suggesting that high oral doses of vitamin B12 might also be an effective treatment.

Individuals with gastrointestinal disorders: Individuals with stomach and small intestine disorders, such as celiac disease and Crohn’s disease, may be unable to absorb enough vitamin B12 from food to maintain healthy body stores. Subtly reduced cognitive function resulting from early vitamin B12 deficiency might be the only initial symptom of these intestinal disorders, followed by megaloblastic anemia and dementia.

Individuals who have had gastrointestinal surgery: Surgical procedures in the gastrointestinal tract, such as weight loss surgery or surgery to remove all or part of the stomach, often result in a loss of cells that secrete hydrochloric acid and intrinsic factor. This reduces the amount of vitamin B12, particularly food-bound vitamin B12, that the body releases and absorbs. Surgical removal of the distal ileum also can result in the inability to absorb vitamin B12. Individuals undergoing these surgical procedures should be monitored preoperatively and postoperatively for several nutrient deficiencies, including vitamin B12 deficiency.

Vegetarians: Strict vegetarians and vegans are at greater risk than lacto-ovo vegetarians and non-vegetarians of developing vitamin B12 deficiency because natural food sources of vitamin B12 are limited to animal foods. Fortified breakfast cereals and fortified nutritional yeasts are some of the only sources of vitamin B12 from plants and can be used as dietary sources of vitamin B12 for strict vegetarians and vegans. Fortified foods vary in formulation, so it is important to read the Nutrition Facts labels on food products to determine the types and amounts of added nutrients they contain.

Pregnant and lactating women who follow strict vegetarian diets and their infants: Vitamin B12 crosses the placenta during pregnancy and is present in breast milk. Exclusively breastfed infants of women who consume no animal products may have very limited reserves of vitamin B12 and can develop vitamin B12 deficiency within months of birth. Undetected and untreated vitamin B12 deficiency in infants can result in severe and permanent neurological damage.

The American Dietetic Association recommends supplemental vitamin B12 for vegans and lacto-ovo vegetarians during both pregnancy and lactation to ensure that enough vitamin B12 is transferred to the fetus and infant. Pregnant and lactating women who follow strict vegetarian or vegan diets should consult with a pediatrician regarding vitamin B12 supplements for their infants and children.

Health Risks from Excessive Vitamin B12

The IOM did not establish a UL for vitamin B12 because of its low potential for toxicity. In Dietary Reference Intakes: Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline, the IOM states that “no adverse effects have been associated with excess vitamin B12 intake from food and supplements in healthy individuals”.

Findings from intervention trials support these conclusions. In the NORVIT and HOPE 2 trials, vitamin B12 supplementation (in combination with folic acid and vitamin B6) did not cause any serious adverse events when administered at doses of 0.4 mg for 40 months (NORVIT trial) and 1.0 mg for 5 years (HOPE 2 trial).

Interactions with Medications

Vitamin B12 has the potential to interact with certain medications. In addition, several types of medications might adversely affect vitamin B12 levels. A few examples are provided below. Individuals taking these and other medications on a regular basis should discuss their vitamin B12 status with their healthcare providers.

Chloramphenicol: Chloramphenicol (Chloromycetin®) is a bacteriostatic antibiotic. Limited evidence from case reports indicates that chloramphenicol can interfere with the red blood cell response to supplemental vitamin B12 in some patients.

Proton pump inhibitors: Proton pump inhibitors, such as omeprazole (Prilosec®) and lansoprazole (Prevacid®), are used to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease and peptic ulcer disease. These drugs can interfere with vitamin B12 absorption from food by slowing the release of gastric acid into the stomach. However, the evidence is conflicting on whether proton pump inhibitor use affects vitamin B12 status. As a precaution, healthcare providers should monitor vitamin B12 status in patients taking proton pump inhibitors for prolonged periods.

H2 receptor antagonists: Histamine H2 receptor antagonists, used to treat peptic ulcer disease, include cimetidine (Tagamet®), famotidine (Pepcid®), and ranitidine (Zantac®). These medications can interfere with the absorption of vitamin B12 from food by slowing the release of hydrochloric acid into the stomach. Although H2 receptor antagonists have the potential to cause vitamin B12 deficiency, no evidence indicates that they promote vitamin B12 deficiency, even after long-term use. Clinically significant effects may be more likely in patients with inadequate vitamin B12 stores, especially those using H2 receptor antagonists continuously for more than 2 years.

Metformin: Metformin, a hypoglycemic agent used to treat diabetes, might reduce the absorption of vitamin B12, possibly through alterations in intestinal mobility, increased bacterial overgrowth, or alterations in the calcium-dependent uptake by ileal cells of the vitamin B12-intrinsic factor complex. Small studies and case reports suggest that 10%–30% of patients who take metformin have reduced vitamin B12 absorption. In a randomized, placebo controlled trial in patients with type 2 diabetes, metformin treatment for 4.3 years significantly decreased vitamin B12 levels by 19% and raised the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency by 7.2% compared with placebo. Some studies suggest that supplemental calcium might help improve the vitamin B12 malabsorption caused by metformin, but not all researchers agree.

REFERENCES

FROM: https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/71/2/514/4729184

Plasma vitamin B-12 concentrations relate to intake source in the Framingham Offspring Study

ABSTRACT